In Uganda, as in much of Sub-Saharan Africa, intimate partner violence (IPV) is widespread. According to data from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics in 2016, 49.9% of ever-partnered women between 15 and 49 reports experiencing IPV at some point in their life, with 29.9% reporting that it happened at some point in the last 12 months (UBOS and ICF 2018).

While there is increasing evidence showing mixed effects from cash transfers to women on IPV, we know less about how economic empowerment through self-employment affects IPV. Both cash transfers and productive self-employment increase women’s incomes. However, income from self-employment depends on women’s skills and effort. This might affect IPV differently from the economic windfalls of cash transfers.

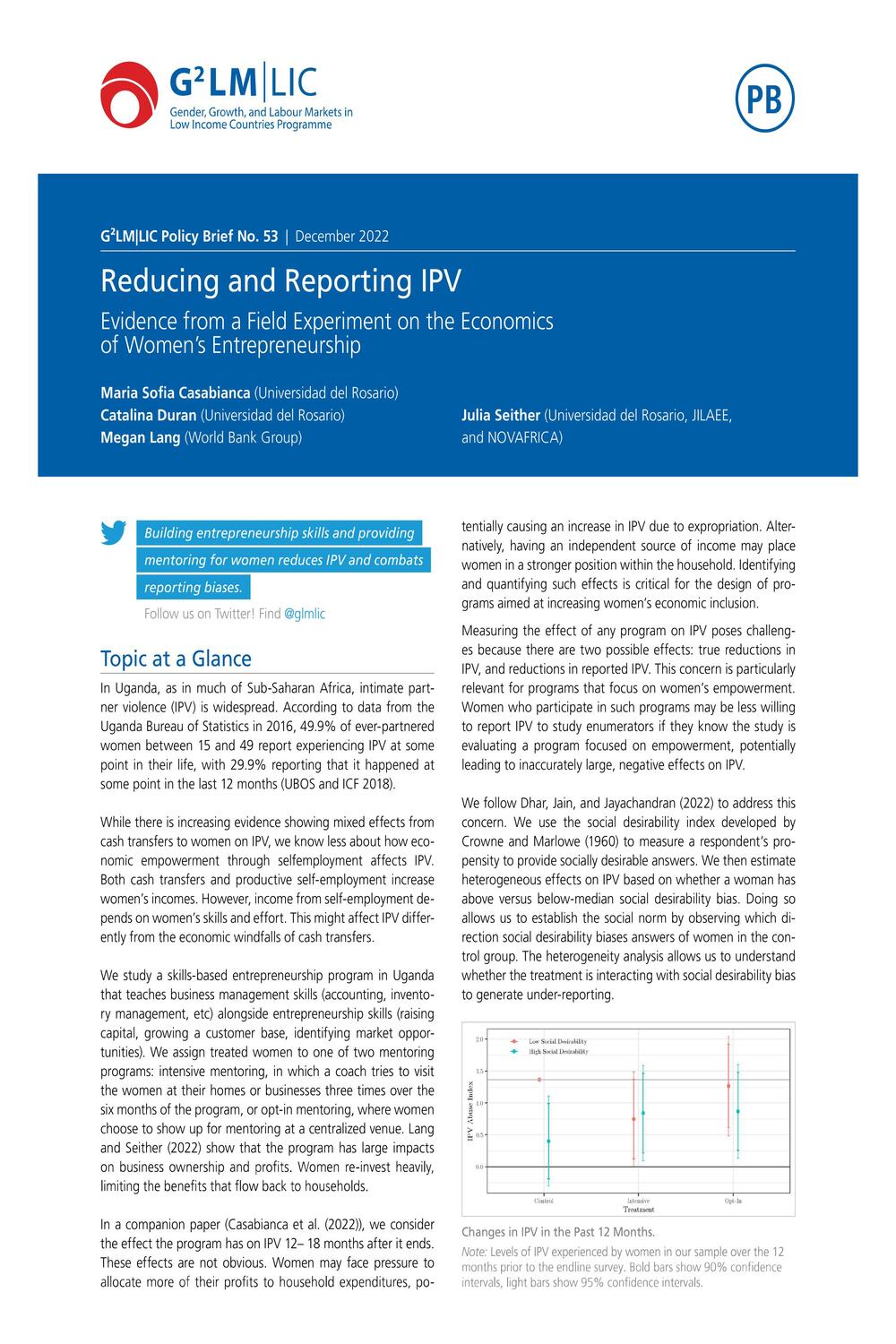

We study a skills-based entrepreneurship program in Uganda that teaches business management skills (accounting, inventory management, etc) alongside entrepreneurship skills (raising capital, growing a customer base, identifying market opportunities). We assign treated women to one of two mentoring programs: intensive mentoring, in which a coach tries to visit the women at their homes or businesses three times over the six months of the program, or opt-in mentoring, where women choose to show up for mentoring at a centralized venue. Lang and Seither (2022) show that the program has large impact on business ownership and profits. Women re-invest heavily, limiting the benefits that flow back to households.

In a companion paper (Casabianca et al. (2022)), we consider the effect the program has on IPV 12– 18 months after it ends. These effects are not obvious. Women may face pressure to allocate more of their profits to household expenditures, poEntrepreneurshiptentially causing an increase in IPV due to expropriation. Alternatively, having an independent source of income may place women in a stronger position within the household. Identifying and quantifying such effects is critical for the design of programs aimed at increasing women’s economic inclusion.

Measuring the effect of any program on IPV poses challenges because there are two possible effects: true reductions in IPV, and reductions in reported IPV. This concern is particularly relevant for programs that focus on women’s empowerment. Women who participate in such programs may be less willing to report IPV to study enumerators if they know the study is evaluating a program focused on empowerment, potentially leading to inaccurately large, negative effects on IPV.

We follow Dhar, Jain, and Jayachandran (2022) to address this concern. We use the social desirability index developed by Crowne and Marlowe (1960) to measure a respondent’s propensity to provide socially desirable answers. We then estimate heterogeneous effects on IPV based on whether a woman has above versus below-median social desirability bias. Doing so allows us to establish the social norm by observing which direction social desirability biases answers of women in the control group. The heterogeneity analysis allows us to understand whether the treatment is interacting with social desirability bias to generate under-reporting.

Reducing and Reporting IPV

Evidence from a Field Experiment on the Economics of Women’s Entrepreneurship

- Megan Lang

- Julia Seither

- Maria Sofia Casabianca

- Catalina Duran